The Historical Evolution of Tibetan Buddhism and the Formation of Its Sacred Canon

Activities Highlights

Tibetan Buddhism is not merely a religious tradition; it is the product of centuries of cultural exchange, political transformation, and meticulous preservation of sacred knowledge. Its history and its scriptures evolved together, shaping one of the most comprehensive Buddhist traditions in the world.

Origins Before Tibet: Foundations in Nepal, India and Central Asia (1st–6th Century CE)

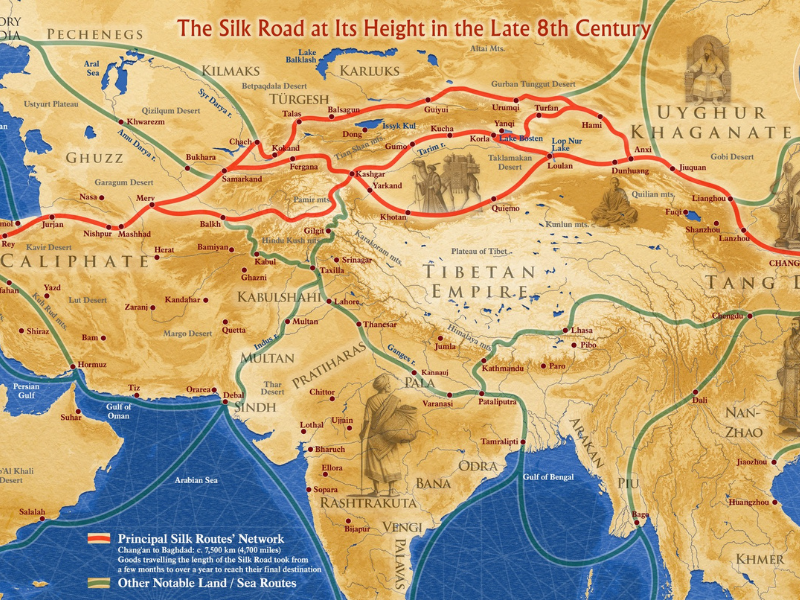

Buddhism originated in India in the 3rd century BCE after the reign of Emperor Asoka, but its philosophical and textual foundations continued to evolve for centuries. By the 1st century CE, Mahayana Buddhism had spread along the Silk Routes during the Kushan Empire into Central Asia and China. These transmission networks passed through regions bordering Tibet, laying the groundwork for Buddhism’s eventual arrival on the Tibetan Plateau.

By the 3rd century CE, Buddhist ideas had begun to influence Tibet indirectly, interacting with the indigenous Bön tradition, particularly in the ancient kingdom of Zhangzhung. While formal Buddhist institutions did not yet exist in Tibet, the conceptual soil was being prepared.

Early Legends and the First Encounter with Scripture (6th Century CE)

Tibetan historical memory preserves symbolic accounts of Buddhism’s first appearance during the reign of King Thothori Nyantsen in the 6th century. According to tradition, sacred Buddhist relics and texts miraculously descended onto the royal palace roof at Yumbulakhang.

Though largely legendary, these accounts reflect an important truth: Buddhism entered Tibet initially as sacred text and symbol, even before organized practice took root.

Imperial Adoption and the Birth of Translation (7th Century CE)

A decisive transformation occurred during the reign of King Songtsen Gampo (618–649), founder of the Tibetan Empire. As Tibet unified politically, it opened itself to religious and cultural exchange with India, Nepal, and China.

Songtsen Gampo’s marriages to Queen Bhrikuti of Nepal and Princess Wencheng of Tang China which brought Buddhist images, artisans, and scriptures into Tibet. During this period, Sanskrit Buddhist texts from India and Nepal were translated into Tibetan for the first time, alongside the development of the Tibetan written script itself. The translated scripture during this period includes: Mahayana Sutras, Dharani (Incantations) and work connected to Avalokitesvara (the bodhisattva later identified with Tibetan kingship). Often cited the first great Nepali Scholar name Buddhabhadra who was a prolific translator who significantly influenced Tibetan Buddhism in broader context of regional Buddhist exchange

Institutional Buddhism and Canonical Foundations (8th Century CE)

Although Buddhism was introduced earlier, it became firmly established during the reign of King Trisong Detsen (755–797). He declared Buddhism the official religion of the Tibetan state and invited leading Indian scholars to Tibet. He also established the first monastery in Tibet called Samye Monastery.

- Padmasambhava: The “Lotus-Born” who used Vajrayāna power to tame local spirits and introduced the esoteric rituals central to the Nyingma tradition.

- Śāntarakṣita: The “Great Abbot” who established the first monastic lineage and integrated rigorous Indian scholastic philosophy into the Tibetan mind.

- Silamanju: The Newar bridge who provided the linguistic expertise to translate the Ratnamegha Sutra and co-authored the definitive rites of Vajrakilaya.

- Vimalamitra: The crown jewel of the Dzogchen lineage who transmitted the “Heart Essence” (Nyingtik) and translated the Guhyagarbha Tantra, the root of all Mahayoga.

Together they founded Samye Monastery, Tibet’s first fully ordained monastery.

At the same time, translation projects accelerated. Texts from Indian traditions—Madhyamaka, Yogācāra, Vinaya, Mahayana sūtras, and early tantras—were rendered into Tibetan. These translations formed the proto-canon, long before a fixed Tibetan canon existed.

Debate, Standardization, and Textual Authority (Late 8th–9th Century)

As Buddhism flourished, debates arose about doctrine and method. A famous philosophical debate at Samye contrasted Indian gradualist teachings with Chinese Chan sudden-enlightenment views. Tibetan tradition records that the Indian approach prevailed, firmly aligning Tibetan Buddhism with Indian philosophical systems.

Under King Ralpachen (r. 817–836), translation terminology was standardized, ensuring accuracy and consistency. This laid the groundwork for later canonical organization.

During this time, collections of Buddhist texts already existed, though the terms “Kangyur” and “Tengyur” had not yet been formally established.

Collapse and Survival: The Era of Fragmentation (9th–10th Century)

Following the assassination of Ralpachen and the persecution of Buddhism under King Langdarma (r. 841–842), monastic institutions were dismantled and state support vanished.

Tibet entered the Era of Fragmentation, marked by political disunity and the decline of institutional Buddhism. Yet Buddhist texts survived through:

-

Family lineages

-

Remote monasteries

-

Hidden teachings (terma) preserved by the Nyingma tradition

The survival of scriptures during this period would later enable a powerful revival.

The Second Dissemination and Canon Formation (10th–12th Century)

The 10th and 11th centuries witnessed a renaissance known as the Second Dissemination of Buddhism. Tibetan kings in western Tibet invited Indian masters and sponsored large-scale translation efforts.

Key figures included:

-

Rinchen Zangpo (958–1055), prolific translator and temple builder

-

Atiśa (982–1054), whose teachings emphasized ethics and systematic practice

During this period, the New Translation (Sarma) schools—Kadampa, Kagyu, Sakya—emerged, alongside renewed scholastic activity.

It was now that Tibet formally organized its vast textual inheritance into two categories:

-

Kangyur — the Words of the Buddha

-

Tengyur — authoritative commentaries and treatises

This structure reflected a uniquely Tibetan solution to preserving Mahayana and Vajrayāna teachings.

The Tibetan Buddhist Canon: Structure and Scope

The Kangyur (Translated Words)

The Kangyur, typically comprising 100–108 volumes, contains texts attributed to the Buddha himself. These include:

-

Vinaya texts on monastic discipline

-

Sūtras, primarily Mahayana but also Śrāvakayāna material

-

Tantras, forming the basis of Vajrayāna practice

Importantly, the Tibetan canon includes tantric texts within the Buddha’s teachings—something not found in earlier Buddhist canons.

The Tengyur (Translated Treatises)

The Tengyur, finalized in the 14th century by Bu-ston Rinchen Drub (1290–1364), contains:

-

Philosophical treatises (Madhyamaka, Yogācāra)

-

Abhidharma texts

-

Tantra commentaries

-

Works on logic, medicine, grammar, arts, and astronomy

Together, the Kangyur and Tengyur preserve over 4,500 texts, making Tibet the greatest archive of Indian Buddhist literature.

Mongol Patronage and Canon Expansion (13th–14th Century)

The Mongol invasion of Tibet in 1240 reshaped Tibetan Buddhism’s political role. Under the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), Tibetan Buddhism became the state religion of the Mongol Empire.

With imperial patronage:

-

Canonical collections were expanded

-

Printing technologies improved

-

Tibetan Buddhism spread across China and Mongolia

During this period, the canon achieved a level of stability and prestige unmatched elsewhere in the Buddhist world.

Gelug Ascendancy and Printing Culture (15th–18th Century)

In the 15th century, Je Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) founded the Gelug school, emphasizing strict monastic discipline and philosophical study grounded in canonical texts.

With the rise of the Dalai Lama institution in the 17th century, the Gelug tradition dominated both religious and political life. Massive woodblock printing projects—especially at Derge—ensured the wide dissemination of the Kangyur and Tengyur

Rimé Movement and Preservation of Diversity (19th Century)

By the 19th century, the Rimé (non-sectarian) movement arose to preserve teachings marginalized by Gelug dominance. Scholars such as Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo and Jamgön Kongtrül collected and printed rare texts, including:

-

Nyingma tantras

-

Kagyu and Sakya transmissions

Without Rimé efforts, many canonical and extra-canonical works might have been lost forever.

Conclusion: A Civilization Preserved in Text and Practice

Tibetan Buddhism developed through a long process of cultural exchange, political change, and disciplined scholarship, evolving in close relationship with its scriptures. From early Indian and Central Asian influences to the great translation projects of the Tibetan Empire and the later formation of the Kangyur and Tengyur, Tibet became the most comprehensive preserver of Indian Buddhist thought. Texts were not merely collected but actively translated, debated, standardized, and practiced, ensuring their continuity even during periods of political collapse and persecution.

This tradition’s endurance lies in its ability to balance preservation with renewal. Successive revivals, imperial patronage, monastic education, printing cultures, and non-sectarian movements allowed Tibetan Buddhism to remain both rooted and adaptive. As a result, it stands today as a living tradition in which philosophy, ritual, debate, and scripture continue to inform one another, preserving a vast intellectual and spiritual heritage that extends far beyond Tibet itself.