The 1952 Swiss Mount Everest Expedition: The Climb That Paved the Way to History

Activities Highlights

Long before the world celebrated the first successful ascent of Mount Everest in 1953, a determined group of Swiss climbers and one extraordinary Sherpa quietly rewrote the limits of human endurance. The 1952 Swiss Mount Everest expedition stands as one of the most important—yet often underappreciated—chapters in Everest’s climbing history. Though it did not reach the summit, it laid the groundwork for all future success on the world’s highest mountain.

Opening Nepal to the World

For decades, Everest expeditions had approached the mountain from North Face, Tibet. That changed in 1950, when Nepal opened its borders to foreigners. This political shift transformed Himalayan mountaineering forever. A British-New Zealand reconnaissance led by Eric Shipton in 1951 proved that Everest could be approached from Nepal via the Khumbu Icefall and Western Cwm, revealing a viable southern route.

Recognizing the opportunity, the Nepalese government granted the first Everest climbing permit via Nepal to Switzerland in 1952.

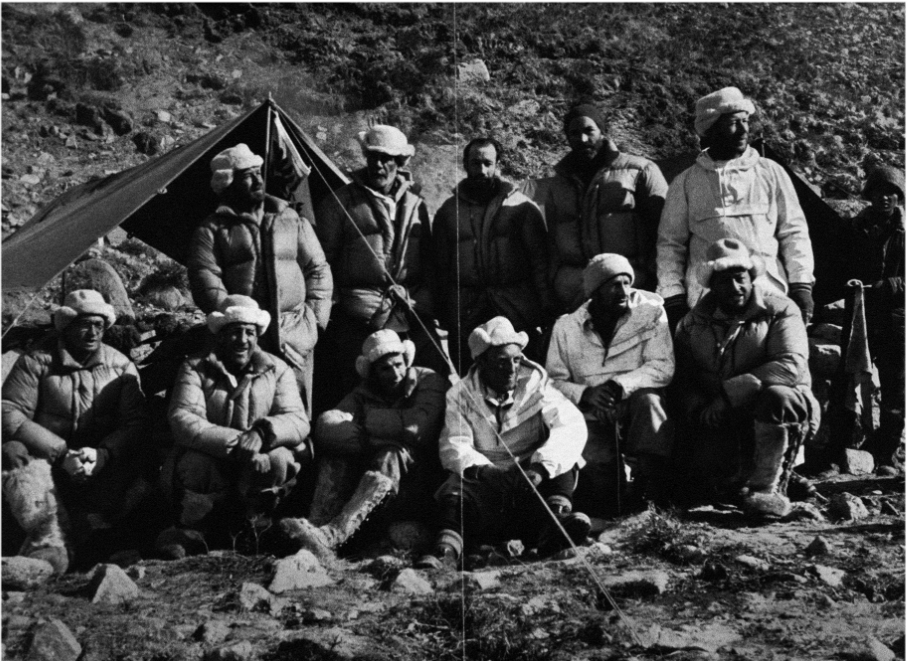

The expedition was led by Edouard Wyss-Dunant, with an elite team of Swiss climbers from Geneva, including Raymond Lambert, René Aubert, Léon Flory, and André Roch. Despite injuries and past frostbite—Lambert had lost toes to earlier expeditions—the team pressed forward.

Among them was Tenzing Norgay, already a highly respected Sherpa climber, whose experience would soon prove pivotal in Everest history.

Backed by the City and Canton of Geneva and supported scientifically by the University of Geneva, the Swiss expedition was exceptionally well organized for its time.

Breaking New Ground on Everest

Building on Shipton’s reconnaissance, the Swiss team successfully navigated the Khumbu Icefall, entered the Western Cwm, and climbed the massive Lhotse Face to reach the South Col—an extraordinary achievement in itself during an era when high-altitude mountaineering was still experimental.

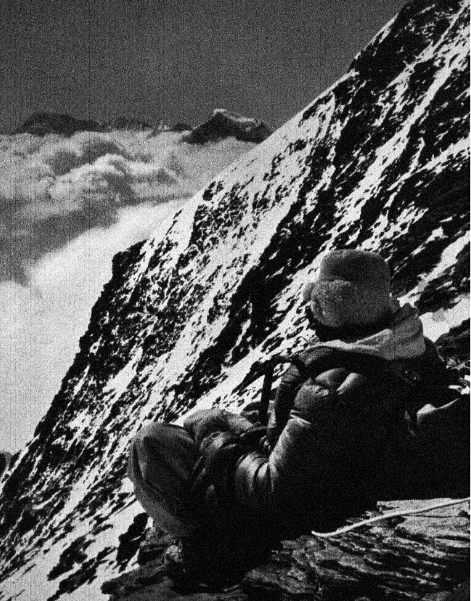

From there, Raymond Lambert and Tenzing Norgay made a bold summit attempt. They pitched a tent at around 8,400 meters (27,500 feet)—the highest camp ever established at that time.

What followed became legendary.

A Night Near the Edge of the World

Lambert and Tenzing endured one of the harshest bivouacs in mountaineering history. They had no sleeping bags, a stove, or functioning oxygen equipment

They survived the night by melting snow over a candle and rationing meager supplies. The following morning, climbing with malfunctioning oxygen sets—or effectively without oxygen—they pushed upward with extraordinary determination.

At approximately 8,595 meters (28,199 feet), just 250 meters below the summit, they were forced to turn back. Exhausted, dehydrated, and battling failing equipment, they had reached the highest altitude ever achieved by humans on Everest.

A Near Victory That Changed Everything

Though the summit remained unconquered, the expedition’s achievements were historic as a new altitude record on Mount Everest. Beside that it proved that the South Col route was viable. A critical insights into oxygen use, hydration, and logistics and Identification of the Geneva Spur, now a key landmark on the South Col route

Later experts—including Edmund Hillary and physiologist Griffith Pugh—noted that dehydration and inadequate oxygen systems were decisive factors. Improved equipment used later might have made the difference.

The Road to 1953

The Swiss expedition’s findings directly influenced the planning of the 1953 British Everest expedition. They confirmed that climbers should ascend the Lhotse Face, establish high camps on the South Col, and improve oxygen and hydration strategies.

One year later, Tenzing Norgay returned, this time alongside Sir Edmund Hillary, and together they stood on the summit of Everest—carrying with them the hard-earned lessons of 1952.

The Autumn Attempt and Lasting Legacy

The Swiss made a second attempt in autumn 1952, the first serious post-monsoon Everest expedition. Battling brutal winter winds and extreme cold, they reached 8,100 meters before retreating. Though unsuccessful, their courage expanded the understanding of seasonal limits on Everest.

The legacy of the 1952 Swiss expedition is undeniable. As historian Marcel Kurz famously noted, it was “almost a victory.”

Conclusion: The Forgotten Triumph

The 1952 Swiss Mount Everest expedition may not have placed a boot on the summit, but it opened the mountain. It transformed Everest from an impossible dream into a climbable reality and forged the path that others would follow.

In the thin air just below the summit, Tenzing Norgay and Raymond Lambert proved that Everest could be climbed—and in doing so, they changed mountaineering history forever.