Heritage Conservation in Kathmandu Valley: Beyond Bricks and Mortar

Activities Highlights

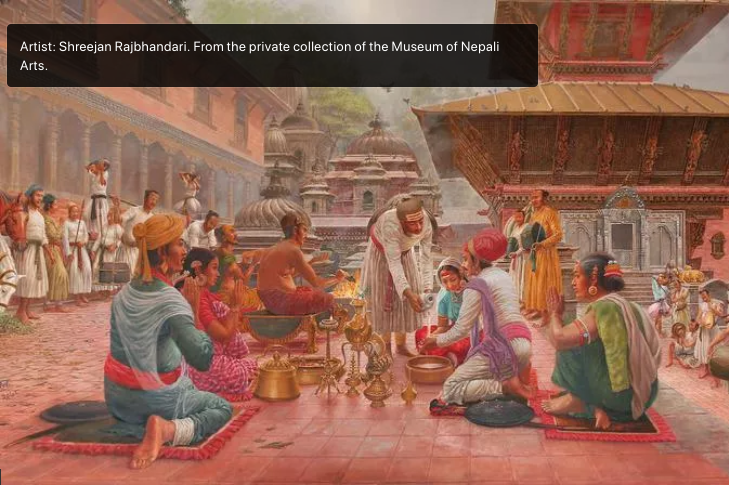

The Kathmandu Valley is not merely a place—it’s a living museum. Its centuries-old temples, majestic Durbar Squares, and sacred sites like Swayambhunath, Boudhanath, and Pashupatinath form the spiritual and historical heart of Nepal. However, as mass tourism, rapid urbanization, and natural disasters increase, these cultural treasures face unprecedented threats.

Moving Beyond Repair: A New Vision for Heritage Conservation

Therefore, heritage conservation must evolve beyond the physical repair of monuments. Instead, it should be rooted in principles that sustain cultural values while effectively managing inevitable change.

Understanding the Need for Heritage Conservation

To begin with, Kathmandu Valley’s historic sites are not just tourist attractions—they embody the soul of a nation. In this context, preserving them means much more than maintaining structures; it means safeguarding evidential, historical, aesthetic, and communal values that define Nepali identity.

For instance, the 2015 earthquake made this painfully clear. Rebuilding efforts weren’t just about replacing bricks; rather, they became a mission to revive Nepal’s cultural identity. As such, heritage conservation must ensure that these treasures continue to live—not as frozen relics, but as vibrant parts of community life.

Core Principles That Guide Heritage Conservation

1. Manage Change to Sustain Values

Undeniably, change—whether due to decay, development, or tourism—is inevitable. Thus, conservation efforts should focus on managing change rather than resisting it.

When reconstructing sites, the following values must be balanced:

- Evidential value (e.g., original materials and techniques)

- Historical value (what the site represents)

- Aesthetic value (visual harmony and beauty)

- Communal value (sacred or social significance)

2. Understand Significance First

Before any intervention begins, it is vital to ask: Why does this site matter?

Consequently, each heritage site should be accompanied by a clear Statement of Significance, including:

- The stories told by the site (e.g., Patan Durbar Square)

- Unique craftsmanship (e.g., Bhaktapur’s intricate woodwork)

- The cultural and spiritual roles the site plays in daily life

By doing so, conservation efforts are guided by meaning, not just materials.

3. Recognize Heritage as a Shared Resource

Importantly, heritage does not belong to governments or tourists alone—it belongs to all, especially the local communities. A traditional example is Kathmandu’s Guthi system, where local trusts maintained cultural sites.

Reviving such community-based models ensures ownership, pride, and sustainability in heritage conservation.

4. Enable Meaningful Participation

Furthermore, sustainable conservation is only possible when the community becomes its custodian. This means:

- Training and empowering local artisans

- Holding inclusive community forums

- Providing accessible documentation in local languages

Ultimately, participatory conservation builds resilience and relevance.

5. Ensure Transparent and Consistent Decision-Making

Too often, corruption and bureaucratic inefficiencies derail genuine efforts. Therefore, conservation policies must be based on site significance, not on political agendas. In doing so, trust and consistency in implementation can be achieved.

6. Document, Learn, and Adapt

Every action matters—and every conservation effort should be thoroughly documented. For example, lessons from sites like Changu Narayan or Bhaktapur must inform future strategies.

Hence, digital archives, periodic impact assessments, and adaptive management approaches are essential components of modern conservation.

Unique Challenges Facing Kathmandu Valley

Urbanization and Encroachment

In recent years, modern buildings have rapidly encroached upon heritage zones, damaging not just the physical sites but also their cultural context. Thus, urban planning must be informed by Principle 2—understanding site significance—to protect buffer zones and ensure sightlines remain intact.

Limited Resources and Skills

Unfortunately, chronic underfunding and a lack of skilled conservators in traditional techniques threaten authenticity. In response, we must:

- Allocate revenue from tourism directly to conservation

- Promote international partnerships

- Train the next generation in indigenous crafts

According to Principles 3 and 4, diversifying resources and empowering local artisans are essential steps forward.

Institutional Fragmentation

Currently, weak coordination and unclear mandates across institutions lead to inefficiencies. As highlighted in Principles 5 and 6, a single, accountable body with clear policies is crucial for success. Moreover, political will must align with a long-term vision that treats heritage as a national asset.

Community Disconnection

When communities feel excluded, conservation efforts falter. Thus, Principle 4 must take precedence—engage locals meaningfully, ensure they benefit economically (e.g., through community-based tourism), and foster cultural pride. Revitalizing the Guthi spirit is a meaningful path forward.

A Way Forward: Integrated Action for Lasting Impact

Clearly, conserving Kathmandu Valley’s heritage is not just about structural repair—it’s about protecting the very soul of Nepal. Therefore, a principle-driven, community-led approach must be prioritized.

Key Actions Include:

- Comprehensive Significance Assessments for all major sites

- Inclusive Governance Structures that reflect community voices

- Transparent and Enforceable Policies grounded in cultural value

- Sustainable Tourism Models that reinvest in conservation

- Urgent Investment in skills training, documentation, and preventive care

- Smart Use of Technology, such as virtual tours to ease visitor pressure

Conclusion: Conservation as a Cultural Mandate

In conclusion, the Kathmandu Valley is a living legacy—a priceless gift from the past to the future. If we act wisely today, it can remain a vibrant, sacred space for generations to come.

Let us move beyond mere repair and adopt a bold, integrated model of heritage conservation—one that is inclusive, transparent, rooted in tradition, and ready for tomorrow.